Legacies of Pride and Shame

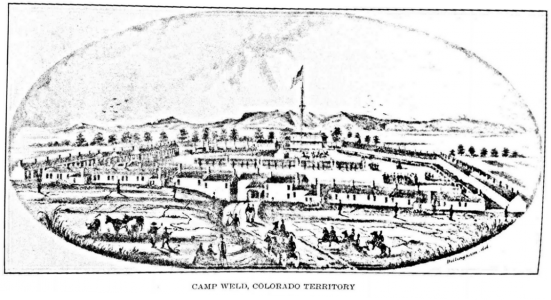

With regard to the history of the La Alma-Lincoln Park neighborhood, there is no lost monument more significant to both U.S. and Colorado history, than the site of Camp Weld. Once located on thirty acres east of the Platte and north of today’s 8th Avenue bridge, it was built on the insistence of 1st Territorial Governor Gilpin in 1861 to help protect the Territory from Southern attack. Situated well on the outskirts of town, just beyond US Marshall Hunt‘s homestead, the camp was used to organize and train troops for the defense of the Union. Colorado’s First Volunteer regiment is credited with beating back the Texan advance, and ending the Confederate ambition of acquiring the mountains of wealth in the West. However, the glory earned at Glorieta Pass in New Mexico would be forever obscured by the Third Cavalry’s shameful legacy, the hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapahoe women and children slain in the Sand Creek Massacre. After two damaging fires, the remaining timber from the camp would find better use elsewhere in town, and the defenders were dispersed to more imminent threats throughout the territory. Then, one thoughtful soldier staked a homestead claim on the land and raised his family in the last standing section of “Officer’s Row.” He planted orchards and built fish ponds on the acreage, operating a market and picnic ground for many years afterward.

A Single Trace Remains

Today, all evidence has been removed from the landscape, but you can still find a bronze and granite marker at 8th and Vallejo. Erected in 1934, the plaque describes the Camp’s legacy, but few notice it or get close enough to read it.

It says:

This is the southwest corner of Camp Weld. Established September 1861 for Colorado Civil War Volunteers. Named for Lewis L. Weld, First Secretary of Colorado Territory. Troops leaving here February 22nd, 1862 won victory over Confederate forces at La Glorieta, New Mexico. Saved the Southwest for the Union. Headquarters against the Indians 1864-65. Camp abandoned 1865.

So much has changed from the early years, that it is hard to picture the military camp that once stood there. It was built along the Platte’s East bank, then about two miles southwest of the city. Buildings were positioned to surround the central square where the volunteer troops could practice their drills, which the townspeople would come to watch for a bit of evening entertainment. From an account in the October 24th Rocky Mountain News, the author elaborates on the camp layout:

“The enclosure embraces about thirty acres…The buildings, which consist of officers’ headquarters, quarters for soldiers, mess rooms, guard house, hospital, etc., occupy four sides of what is nearly a square, and built in the most substantial and comfortable manner. The building space occupied by each company is 180 feet, divided into mess rooms which are 30 by 18 feet, with huge fireplaces at either end, and sleeping apartments of the same size, capable each of accommodating 25 men…The main entrance to the camp enclosure is on the eastern side. Immediately in front, after passing in, is the Guard House, a commodious building, standing isolated from the main range of barracks…Running entirely around the enclosure, and twenty-five feet from the buildings, a top rail fence is being constructed,”

The Camp was named for the first Territorial Secretary, Lewis Ledyard Weld. Invested with significant responsibilities, it was considered a prominent appointment in the day. Originally arriving in Denver in 1860, Weld soon after sought the leadership position in Washington after becoming frustrated by the lack of a justice system here in which to practice law, and was named to the post by President Lincoln. Like Governor Gilpin, he served briefly as an able and respected administrator, though unlike him, had little to do with the camp itself. The Secretary’s uncle, Theodore D. Weld was a prominent abolitionist, and likely influenced his nephews’s decision to return east and join the Union Army as Captain of the 7th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops. Evidently an able officer, Weld was promoted to Major, then Lt.Colonel of the 41st Colored Infantry, participating in battles at Deep Bottom and Russell Mills. Unfortunately, he expired in a hospital on the Appomattox from exposure and an unrelenting cold in January 1865, (Hafen, 1942).

Is the West North or South?

Colonel William Gilpin was also appointed to the office of Territorial Governor by President Lincoln, and immediately sought to address the Southern threat to the newly created Colorado Territory. The region’s earliest gold seekers were from Georgia, and though many new-comers with city-building in their hearts were mid-Western Yanks, there were some notable residents supporting the rebellion, including Mayor Moore and Postmaster McClure. In April, handsome rebel ringleader Charlie Harrison raised a Confederate flag atop Wallingford and Murphy’s General Store before Sam Logan climbed up to bring it down. Numerous bar brawls and street skirmishes ensued in the early months after Fort Sumter. General Sibley’s plan to recruit a brigade of Texans to march up the Rio Grande was on the lips of Denver citizens by summer. Loyalty oaths were sworn to demonstrate allegiance to the Union. In fact, most were loyal to the Union and many Southerners returned home for the fight, but in May of 1861 when the Governor arrived, rumor and boasting added to the fog of war. It was believed at the start that sentiment was fairly evenly split, feeding Gilpin’s overwhelming sense of urgency while the remaining secessionists were eventually run out of town.

Governor Gilpin worked diligently in establishing the infrastructure of government and preparing for the pending battle. Denver and the West were a plum, ripe for the South’s picking. Pike’s Peaks were still presumed to be filled with unlimited riches, and considered potentially pivotal for either side to possess. Gold rich California was disgruntled from being under-served by Washington DC, and Oregonians apparently shared this view. The Mormons of the Utah Territory owed even less allegiance to the Union, and perhaps some bitterness. New Mexico was similarly divided as Colorado seemed. For the South, Pacific ports offered the opportunity to bypass the eastern blockade, and to access trade with China and beyond. Strategically, Confederate gains in the West would be Union losses. Despite having little population for a territory, the timing of it’s formation supports the idea that we were indeed considered significant.

Regardless the actual validity of the threat, the Governor had no orders or financial backing with which to build his defense. There was no treasury or regular taxation established, and DC had other pressing priorities. Invested only with the authority of his office, Gilpin took it upon himself to draw up drafts on the U.S. Treasury to pay for the construction of Camp Weld, and the recruitment and outfitting of it’s regiments. Within the first year, after the unauthorized notes were traded widely in Denver, they eventually reached the offices of the U.S. Treasury for payment. Given the pressing needs of the war closer to the nation’s Capitol, the Department refused to honor the drafts as legal tender. The news caused the bubble to burst at home, and Gilpin was invited to DC for an accounting. The Treasury eventually paid the merchant accounts that could show adequate records, but tough times were made worse for a lot of folks around town that put their faith in the Goverrnor and his illegal drafts. In the end, Gilpin’s primary accomplishment of saving the West for the Union would lead to his removal from office, and to the appointment of our second Territorial Governor, Dr. John Evans. Passing in 1894, Colonel Gilpin lived the remainder of his days in Denver, a friendly face often recognized on a street corner, always eager to converse with passers-by, and usually indulged like an eccentric uncle.

Though many questioned his authority, few doubted his sincerity. The Governor was both a West Pointer, a Western scholar, and well-connected politically. He was a firm believer in “Manifest Destiny,” that America, for her virtues is ordained to stretch from sea to shining sea. Further, he promoted a more obscure theory that placed Denver City in a geographical line with the “isothermal axis of the universe,” the heir apparent in the progression of civilization with other great cities across the globe and throughout history (Perkin, p.233). Gilpin was confident that Denver was destined for greatness, and felt obligated to protect it for America’s bright future.

Circulated around Denver before reaching DC, this currency inflated a depressed economy. (Smiley, 1901)

Gilpin’s“Pet Lambs”

Most of Gilpin’s recruits descended from the mountains, gold-less and ready for a fight. By 1861, it was already clear that mineral riches were not as easy to acquire as many had expected. As most accounts recall, before they were summoned to battle, “Gilpin’s Lamb’s” terrorized this saloon filled city, helping themselves to scarce supplies. Given the non-existent funds for salaries, some volunteers felt obligated to exact some payment for service. From the Rocky Mountain News, in an article headed Disorderly Soldiers, we learn the irony of the gentle nickname he used for his recruits:

“The conduct of some of the soldiers from Camp Weld, when on liberty in this city, is becoming a matter of serious complaint amongst our business men. Hardly a day passes when we do not hear of some outrage, committed by soldiers under the influence of liquor. Stores are entered, property seized upon and appropriated, and threatening language and violent demonstrations used, if remonstrances are made. This state of affairs has continued long enough. Those saloons which furnish soldiers with liquor ought to be cleaned out at once, and their proprietors provided with lodgings on Larimer street. Our citizens will not much longer submit to the outrages which have lately occurred almost daily, and serious consequences will surely follow, if the soldiers are not in some way restrained,” (RMN,10/3/1861)

A personal account from nearby neighbor, Isa Hunt Stearns, recalls more bad behavior, and the impact the “lambs” had on the city:

“Much annoyance and discomfort and actual fear was caused our family by the U.S. soldiers stationed near our home. They stole everything they could lay their hands on and at night drunken soldiers demanded admittance and beat the doors and blinds, thinking the house to be the barracks. Our only protection when we heard voices or footsteps was to extinguish the lights, until, discouraged, the drunken fellows departed…One afternoon when my father was absent on one of his long trips, three drunken officers all cut and bleeding, came to the house and demanded a search of the premises for some deserters. In spite of Mother’s protestations they entered, swearing and quarreling. In the midst of it, in walked my father, and his anger can well be imagined. He, at once, gave my mother a pistol; and taught her to shoot. Reporting the offense of the soldiers at headquarters, he told them that he had instructed his wife to shoot any soldier who entered her door. Be it added, the offense was never repeated. It seems the officers had the deserters, but when drinking and quarreling among themselves, lost their prisoners.”

By 1887, a newspaper article shows how some citizens looked back with some good humor on the soldiers’ follies,:

” A good many night alarms were turned in at Camp Weld, but it is said that the camp was never really attacked. There was a sprinkling of deserters from the regular army among the men, and these fellows, who were well up on the tricks of the trade, took the new men under their wings and gave them military training of a very doubtful character. The men were forbidden the use of whiskey, but would have it at any risk; new schemes were constantly devised to secure it, and the regular army deserters were very prolific in inventions where whiskey was concerned…These same soldiers, too, had habit of what they called ‘pressing.’ That is, they stole everything they could lay their hands on, no matter whether it were any use them or not…One man walked half a mile to steal a three-legged stool. When asked sternly by the officer why he stole it, he admitted that the stool had no use, but that he only ‘pressed it to keep his hand in,'”(The Republican, 3/14/1887).

In January 1862, Gilpin’s worst fear was finally realized when news came of the coming invasion and idle pursuits would be (temporarily) abandoned for marching and fighting. After struggling to collect all the supplies and men he wanted, Sibley finally was on the march to Denver, departing from San Antonio in December with 3700 men.

Glory at Glorieta

Action at Apache Canyon painted by Domenick D’Andrea

Proceeding up the Rio Grande Valley, General Sibley’s men first captured Forts Fillmore, Thorn, and Bliss unchallenged before approaching Fort Craig in New Mexico. Union General Canby’s troops were stationed there and hoped to hold the invaders at bay. Sibley intended to use the fort to regroup and recruit in Albuquerque and Santa Fe. In the midst of the mountainous terrain, a Union detachment attempted to take advantage of the rebels’ long dry march, and prevent Sibley’s men from accessing the refreshment of the river at the crossing point. There, the Battle of Valverde was fought, and the Union troops were left defeated by the Texans. Advantage Confederacy.

Emboldened by victory and quenched thirst, Sibley set his sights further north along the Santa Fe Trail, by-passing Fort Craig and General Canby. Proceeding toward Fort Union, he easily occupied both Albuquerque and Santa Fe, but fortunately, locals were not as willing to join the fight as Sibley had anticipated. Warfare in the West proved different than many experienced in more close-knit Eastern states. Supplies and recruits were much harder to come by, and both sides believed that possession of Fort Union, and her stockpile of munitions, would be the key to victory.

Though largely occupied by fighting closer to home, the Federal Army did have two volunteer regiments authorized in the New Mexico Territory, in addition to the 1000 “regular” troops lead by Canby. Two more regiments were commissioned from the Colorado Territory, but were to be raised in Cañon City, and lead by Captains T.H. Dodd and James H. Ford. After Glorieta, those men would largely comprise Colorado’s 2nd regiment. Meanwhile, Gilpin was working on recruiting the First. The Officers of the First Regiment Colorado Volunteer Infantry are worth noting here, as many will be recognized today:

Colonel John P. Slough, Lt. Colonel Samuel F. Tappan, Major John M. Chivington, Captain E.W. Wynkoop, Captain S.M. Logan, Captain Richard Sopris, Jacob Downing, Captain Scott J. Anthony, Captain S.H. Cook, Captain J.W. Hambleton, Captain George L. Sanborn, Captain Charles Mailie, and Captain C.P. Marion. Several have Denver streets named after them, Sopris, a mountain, and Chivington, a town. Chivington features most prominently in this tale, so it should also be noted that he declined the role of Chaplain in favor of a fighting position when the company was formed, (Smiley, p378).

By February 10th orders reached Camp Weld, and Slough and the Colorado volunteers decamped for Fort Union in New Mexico. The regiment, with wagons and wives in tow, marched forty furious miles a day, reaching the Fort by March 11th, 1862. They had some time to recover, cavort, and prepare before their offensive would begin.

March 26th marks the first day of the engagement. Unknown to each other, Slough headed south from the fort with 1342 men while Confederate Colonel Scurry was leading 1100 men north from Santa Fe. Major Chivington lead a scouting advance of 400. Though his orders were to resist engaging the enemy, after capturing twenty Texan scouts and learning of the Confederate army entering Glorieta Pass from the south, he proceeded onward to Apache Canyon. There he encountered and attacked Major Pyron’s advance of 500 men, and won the day. Fighting for three hours, Chivington’s bravery in battle was noted and the men from the mountains would begin their reputation for ferocity. The Rocky Mountain News would later publish an account written from a captured Texan to his wife:

“On the twenty-sixth, we got word that the enemy were coming down the canon, in the shape of two-hundred Mexicans and about two-hundred regulars. Out we marched with two cannons, expecting an easy victory, but what a mistake. Instead of Mexicans and regulars, they were regular demons, that iron and lead head no effect upon, in the shape of Pike’s Peakers from the Denver City Gold mines…before we could form a line in battle, their infantry were upon the hills, on both sides of us, shooting us down like sheep…They had no sooner got within shooting distance of us, than up came a company of cavalry at full charge, with swords and revolvers drawn, looking like so many flying devils. On they came to what I supposed certain destruction, but nothing like lead or iron seemed to stop them, for we were pouring into them from every side like hail in a storm. In a moment these devils had run the gauntlet for half a mile, and were fighting hand to hand with our men in the road…some of them turned their horses, jump the ditch, and like demons, came charging on us. It looked as if their horses’ feet never touched the ground…Had it not been for the devils from Pike’s Peak, this country would have been ours…”(Perkin, p.248). Advantage Union.

Burning of Wagon Train at Apache Canyon. Painted by Roy Anderson

Armistice ruled the next day while both sides got reinforced. Slough and about 700 men joined Chivington at Koslowski’s Ranch on the Pecos River, while Colonel Scurry joined Pyron’s remaining forces.

Nearly equally matched, an unusual strategy and another great day for the Major would prove fortuitous for the United States. Chivington was again given the task of leading a detachment. The men in his command would travel east across mountainous terrain, aiming for the rear of the Rebel force from the southern entrance to Apache Canon. Meanwhile, Slough’s 700 troops would take the onslaught from the front. As Chivington reached the peak overlooking the Confederate supply wagons, his comrades were losing the fight on the battlefield. They charged down the mountain, overtook the guard, set fire to the wagons, bayoneted beasts, and laid waste to the artillery. On word of Slough’s retreat to Koslowski’s ranch, Chivington’s men marched back through mountains in darkness.

A truce was called to allow both sides to regroup, but the battle was over the moment Sibley learned of his supply wagons’ destruction. From Santa Fe, the Texans would retreat south along the Rio Grande, with Canby leading the Colorado men in pursuit. Chivington would be promoted to replace Slough as Colorado’s Military District Commander.

The Camp Weld Council

If the context of US history surrounding Denver’s birth addressed the great debate over the practice of human bondage, Colorado also offered the country a chance to question the righteousness of our imperial destiny. And, much like the circumstances surrounding the Civil War, treatment of the native population had long been a difficult and controversial issue for the United States government and its people.

While this stretch of rocky land Jefferson purchased from France was thought uninhabitable, Americans rushed straight through to California. Without delving into the long history of Native American displacement here, Cheyenne and Arapahoes were pushed south and west, and by the terms of 1851’s Treaty of Fort Laramie, could safely roam most of what is now Eastern Colorado into parts of Kansas, Wyoming, and Nebraska.

Ten years later, the Treaty of Fort Wise would shrink the reservation beyond sustainability, and signed by only 6 of 44 chiefs, would further splinter tribal leadership. Ten days after that “agreement” was reached, the Colorado Territory’s formation brought much more Federal focus to the region.

After Glorieta, Camp Weld troops were off in service to the Union far from Denver, combating rebel uprisings in Texas and Kansas territory, and keeping travel safe on the Santa Fe Trail. When new Territorial Governor Evan’s attempt to council with tribal leaders in July 1863 was insultingly unattended, a new course was set. It was thought that tribes were uniting and resolute on fighting to the end. He fervently lobbied Congress for the formation of a third regiment to protect the Capitol city. The Third’s authorization was seen as a US declaration of war, and marked a political turning point for the Governor. Full statehood for Colorado would eventually lead to seats in the Senate and Congress, and Evans was likely positioning to grasp the mantle.

Sourced from kclonewolf.com

The formation of Colorado Cavalry’s Third would be limited to 100 days, empowered only to protect against an immediate threat. Evans’ ally, Colonel Chivington, was fatefully placed in charge of the new regiment. He was a war hero with Congressional aspirations of his own, already commander of the Colorado Military District and like Evans, armed in friendship with Rocky Mountain News proprietor, William Byers. The “Fighting Parson” immediately instituted martial law to help stimulate recruitment. It shouldn’t strain credulity to say that many folks here favored a “kill or be killed” strategy when it came to the “Indian problem,” and Chivington was a vocal supporter of this view. In a sermon given August of 1864, he inspired the slogan “Nits Make Lice” and declared his policy to “kill and scalp all, little and big,” (Perkin, 1959, p.269).

However, not all citizens trusted Chivington’s fervent judgement. Some believed that a non-violent approach was more justified, given the friendships achieved despite so many broken promises. It was understood that buffalo hunting grounds, as well as access to life-giving water, were integral to the Native Americans’ more nomadic way of life. Each treaty simply “legitimized” the settlers encroachment onto previously recognized reservation land. In describing the atmosphere of the territory, US Marshall Alexander C Hunt commented in his congressional testimony in late1864:

“That feeling [extermination] prevails in all the new countries when the Indians have committed any depredations. And more especially will people fly off the handle in that way when you exhibit the corpse of some that has been murdered by the Indians. When they come to their sober senses they reflect that the Indians have feelings as well as we have, and are entitled to certain rights; which, by the way, they never get” (Berwanger, p18).

He refers almost specifically to the Huntgate murders of June 1864, in which the mutilated white victims were displayed in town, which served only to inflame feelings of fear and revenge. Reports indicated the strength of the warring factions over those peaceably inclined, matching the raging sentiment in the city.

On August 10th citizens would read the governor’s “Appeal to the People” in the Rocky Mountain News:

“Patriotic Citizens of Colorado:- I again appeal to you to organize for the defense of your homes and families against the merciless savages…Let every settlement organize its volunteer militia company for its defense…Any man that kills a hostile Indian is a patriot; but there are Indians who are friendly, and to kill one of these will involve us in greater difficulty… Jno. Evans” (RMN, 8/10/1864)

Winter had traditionally brought peace, as treaty-promised food and supplies were needed to survive starvation and disease. In summer, attacks always resumed and Denverites were growing tired of the routine.The Cheyenne’s Dog Soldiers and other Sioux warriors refused to recognize any treaties, and continued to encounter and confront travelers and settlers. In the Civil War, many tribesmen saw opportunity to make a stand, with whites weakened by fighting among themselves. In the end, the “warriors” on both sides poisoned the politics between the two societies by striking at innocents. As the situation escalated, even those wishing for peace found it difficult to trust recent alliances or assurances.

By autumn, the Rocky Mountain News could be said to be fanning the flames with rhetoric, “The most revolting, shocking cases of assassination, arson, murder and manslaughter that have crimsoned the pages of time have been done by Indians…”(RMN, 9/7/1864), Justified by a growing list of theft, murders, and “depredations”, many constituents saw the extermination of an enemy as the only solution. People jeered at the “Bloodless Third” regiment for its lack of action, and Chivington was determined to lead his men to new glory. In late September, his opportunity arrived. Seeking peace, Cheyenne Chiefs Black Kettle, White Antelope, and Bull Bear came to Denver. With them were the Arapahoes Neva, Bosse, Heap Buffalo, and Na-ta-nee. Perhaps dubious of the Chiefs’ intentions, Evans said his authority to negotiate had been altered, and suggested they surrender to the military at Fort Lyon. Chivington’s presence at the “Camp Weld Council” suggests the inception of a sinister plan, and few would believe that Evans was ignorant of it.

Photograph taken after the Camp Weld Council, September 28, 1864. Standing L-R: Unidentified, Dexter Colley (son of Agent Samuel Colley), John S. Smith,

Heap of Buffalo, Bosse, Sheriff Amos Steck, Unidentified soldier.

Seated L-R: White Antelope, Bull Bear, Black Kettle, Neva, Na-ta-Nee (Knock Knee).

Kneeling L-R: Major Edward W. Wynkoop, Captain Silas Soule. Courtesy Denver Public Library, Western History Collection X-32079

The Cheyenne and Arapahoes returned to the reservation, about 250 miles southeast from Denver. Black Kettle was instructed by the soldiers to stay within watch and aid no enemies, and so set up camp about forty miles north of Fort Lyon. The little Sand Creek village had surrendered and the inhabitants believed they had the protection of the US military.

Before his hundred day commission was up, Chivington departed Camp Weld, even though there had been no reports of hostilities. Shutting down mail service allowed him to reach Fort Lyon with secrecy, offering further evidence of his intended ambush. On November 28th, at 8 o’clock in the evening, about 950 well-armed and eager men marched toward the peaceable camp in darkness. While most soldiers were ignorant of the set up, it was alleged that Chivington reminded men of the atrocities, and of the obligation to protect wives and children at home. Modern descriptions of the bloody scene suggest that 500 escaped, while 200 women, children and elderly were brutally massacred and mutilated.

Chivington’s account to Major General Curtis dated November 29th, portrayed things differently:

“We made a forced march of forty miles, and surprised, at break of day, one of the most powerful villages of the Cheyenne nation…killing the celebrated chiefs One Eye, White Antelope, Knock Knee, Black Kettle, and Little Robe, with about five hundred of their people, …making almost an annihilation of the entire tribe…”

He concluded the letter with an interesting preemptive line of defense,

“I will state, for the consideration of gentlemen who are opposed to fighting these red scoundrels, that I was shown, by my chief surgeon, the scalp of a white man taken from the lodge of one of the chiefs, which could not have been more than two or three days taken; and I could mention many more things to show how these Indians, who have been drawing government rations at Fort Lyon, are and have been acting,” (RMN, 12/8/1864).

The “Bloody Third” returned to Denver on December 22 in glory, however word of the atrocities reached Washington before the end of the year. The many scalps and sadistic souvenirs that paraded through the city may have been the tip off. On December 30th the News reported a Congressional investigation would be launched based on “letters received from high officials in Colorado” reporting “the Indians were killed after surrendering and that a large proportion of them were women and children,” (RMN 12/301864). Locals were outraged by the scrutiny, but the commission would strongly condemn both Evans and Chivington:

“…From the suckling babe to the old warrior, all who were overtaken were deliberately murdered. Not content with killing women and children, who were incapable of offering any resistance, the soldiers indulged in acts of barbarity of the most revolting character…It is difficult to believe that beings in the form of men, and disgracing the uniform of United States soldiers…could commit…such acts of cruelty and barbarity.” (Joint Committee Report on the Conduct of the War, 1865).

Chivington left Denver in disgrace, but returned ten years later to die. Evans remained a pillar of the community, but never acquired the seat in the Senate he coveted. Hostilities persisted, and war on the plains would ensue for decades, with Cheyenne and Arapahoe warriors conquering Colonel Custer at Little Big Horn in 1876.

A Homestead and a Historian

Camp Weld building painted by local artist Herndon Davis in 1940. Courtesy DPL, Western History Collection Z-2934; C41-8 ART

By September 1864, several months before the conclusion of the Civil War, Elisha Milleson of the First Cavalry regiment had noticed that the camp was nearing the end of its service. The first to file a homestead claim, and already living in quarters with wife Lydia and three sons, they remained in a section of barracks while the rest of the camp was disassembled for salvage. The Millesons converted the surrounding 80 acres into a park-like paradise. He supplied his busy farmer’s market with the orchards, fishponds, and assorted fields of fruits and vegetables he cultivated. Well regarded by the community, he and his wife would often help chaperon church picnics on the grounds. Milleson’s Pond was also a favorite swimming hole on hot summer days, and remembered fondly for winter skating parties.

A final post script should mention the Sanford family and a relevant contribution to the neighborhood. Byron Sanford was also a soldier at Camp Weld. He served in the First Infantry at Glorieta, and his wife’s diary offers us a first-hand account of a woman’s life in the camp and on the road in support of the troops:

“The hospital accommodations at Camp Weld are quite limited. I went the other day to see twenty-one soldiers that had been stricken with snow blindness while on a scouting trip. The poor fellows are in a darkened room. The surgeon said that they must have shades made of green cloth to wear over their eyes. I went to all efforts, but could not find any kind of green cloth, but I had a green, satin parasol, almost new, and cut it up to make all the green shades for the afflicted soldiers,” (Sanford, 1930).

A son was born to the Sanfords while living in Camp Weld, and Albert B. would grow up to celebrate Denver’s pioneers as Assistant Curator of History of the State Historical Society. His writings are responsible for much of what we know about our neighborhood’s early history and his efforts were instrumental in erecting the monument at 8th and Vallejo in 1934.

Sources

Berwanger, Eugene H., “The Rise of the Centennial State: Colorado Territory 1861-76”, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 2007.

Gregg, Isa Stearns, “Reminiscences of Is Hunt Stearns,” The Colorado Magazine, Vol.XXVI, No.3,p 183-193, State Historical Society of Colorado, 1949.

Hafen, LeRoy R, “Lewis Ledyard Weld and Old Camp Weld”, The Colorado Magazine, Vol.XIX, No. 6, p.201-7 Denver CO, November 1942.

“Massacre of the Cheyenne Indians” – United States Congress, House of Representatives Joint Committee Report on the Conduct of the War, 38 Cong., 2 sess., Washington, Government Printing Office, 1865.

Perkin, Robert L, “The First Hundred Years”, Denver Publishing Company, Denver, 1959.

“Sand Creek Massacre”, http://www.kclonewolf.com/History/SandCreek/sc-index.html WAY MORE INFO

Sanford, Albert B., “Camp Weld,” The Trail, 17:14, p.14-15,Nov, 1924.

Sanford, Albert B., “Camp Weld, Colorado,” The Colorado Magazine, Vol.XI, No.2, p.46-50,Historical Society of Colorado, 1934.

Sanford, Albert B, ed.,”Life at Camp Weld and Fort Lyon in 1861-1862 : An extract from the Diary of Mrs. Byron Sanford,” The Colorado Magazine, Vol.VII, No. 4, Historical Society of Colorado,1930.

Smiley, Jerome C, “History of Denver : With outlines of the Earlier History of the Rocky Mountain Country”, Times-Sun Pub. Co., Denver, 1901.

Denver Post

10/30/1932, “Old Building in Denver is All that Remains of Camp Weld”,

5/4/1949, “Civil War Camp Site Uncovered By Workers,” p.43

6/26/1960, “History Was Forged at Obscure Denver Site,” p.22A

The Denver Republican

3/14/1887, “Memories of Camp Weld,” p.8

10/2/1888, “A Ride in Suburban Denver,” p.2

Rocky Mountain News

9/19/1861, “Parade at Camp Weld,” p.2 c.1

10/1/1861, “Barracks”, p3. c.1

10/3/1861, “Disorderly Soldiers,” p.2 c.2

10/24/1861, “A Visit to Camp Weld,” p2. c.2

2/24/1862, “Sketch of Camp Weld,” p.3 c.2

8/10/1864, “Appeal to the People,” p.2 c.1

9/9/1864, “Fire in Camp Weld,” p.2 c.1

9/29/1864, “Indian Council,” p.1 c.1

12/8/1864, “Great Battle with the Indians!” p.2 c.2

12/30/1864, “The Fort Lyon Affair,” p.2 c.1

2/23/1934, “Monument Dedicated on Site of Camp Weld”, p.20

4/22/1934, “Relic of 1881 Post Remains: House at 8th and Vallejo Once Part of Army Quarters,” p.E6

Pingback: “The only wagon road running southward entered Denver by way of Ferry St…” | Across the Creek

Pingback: Episode 10 Camp Weld: Marking (and hiding from) Denver’s Past | Delve Denver Podcast

Pingback: Maps to Lincoln Park’s History | Across the Creek